57 Meditations on Kicking @$$ in Business and Life"4.8/5 stars" on Amazon

Integrity Expert Al Watts On Penn State, BP & More

Tweet CommentI recently met Al Watts, author of Navigating Integrity: Transforming Business As Usual Into Business At Its Best.

Al was kind enough to do a quick Q&A (between sailing trips) with me on the topic of business integrity.

Captain Al on his sloop LOON on Lake Superior

Q: Hi Al. Would you give a quick definition of each of your “4 Pillars Of Integrity” …

No comments yet | Continue Reading »

Wednesday, September 7th, 2011

Business Is Like A Decathlon: Be Decent At These 10 Things & You’ll Win The Gold!

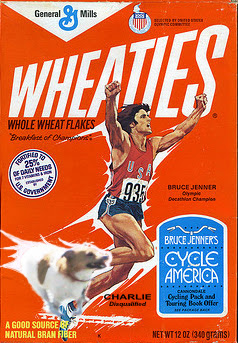

Tweet 1 CommentI’d love to see your face on a box of Wheaties.

The Olympic decathlon — a combined event of 10 different track and field races — is a perfect metaphor for business.

Bruce Jenner didn't have to win every one of the 10 races in the Olympic decathlon to win the gold.

You can actually win the decathlon without being the best at any of the 10 races.

In fact, Bruce Jenner (winner of the 1976 Olympic Decathlon and pictured on the Wheaties box) averaged the equivalent of a little better than 3rd place in each race — and he still won the decathlon by a substantial margin.

Inspired by the decathlon metaphor, here is a 10-item checklist for succeeding in business…if you train to place in these 10 business races, you can win the business gold. …

1 comment so far | Continue Reading »

Wednesday, April 6th, 2011

HR Star Explains How To Cruise The Career S-Curve

Tweet 3 CommentsThe January-February 2011 Harvard Business Review featured an article titled Reinvent Your Business Before It’s Too Late: Watch Out for Those S-Curves.

A Standard S-Curve

Seeing this headline caused my mind to immediately jump to my study of S-curves in graduate school (think of an S-curve (see chart above) as the graphical life of an organization where performance ascends (“replicating and improving”), often rapidly, but later declines (“dying”) due to stagnation, new market entrants, tired management etc.). …

3 comments so far (is that a lot?) | Continue Reading »

Sunday, May 23rd, 2010

7 Tips On How To Motivate Your Team (Hint: Make Them Feel "Progress")

Tweet 4 CommentsA feeling of “progress” may be the most important motivator for you or your team, according to a Harvard Business Review study on what motivates people (thanks to my colleague Mary for pointing this one out).

The HBR study took an interesting angle on motivation by studying hundreds of workers and digging into what happens on a great work day.

The gist of the study is that on days when workers feel like they’re making progress on projects their emotions are positive and that increases their drive to succeed.

The opposite is true: when workers are feeling like they’re on the “hamster wheel,” working hard with little in the way of results, they feel negative emotions and their performance plummets.

And the progress that your team feels can even be small…and they’ll still feel motivated!

7 Tips For How To Motivate Your Team Through Progress

1) Set SMART Goals

To motivate your team through the feeling of progress, you’re gonna first need to work with them to set goals.

The goals you set should be SMART Goals:

- Specific — Well defined, clear to everyone

- Measurable — There should be a metric or some measurement to identify how you’re progressing on your goal.

- Agreed-Upon — The goal should be agreed upon by the people working on it.

- Realistic — The goal can be ambitious but should be within reason

- Time-based — Every goal should have a time-line.

2) Provide Resources Necessary to Achieve Goals

You as a leader should do whatever you can to provide the resources necessary for your team to work on reaching goals.

Spend 1-on-1 time with them to discuss the goals and ask them what they need to reach them.

3) Hold Frequent Meetings To Chunk Down Goals

Let’s say you’ve got your team’s quarterly goals in place.

Now you’re gonna want to set up frequent meetings within the quarter to discuss them.

I recommend that you meet with your team either daily (or every other day) (see Daily Huddle).

In those huddles, ask your direct report to list things that they could do in THAT WEEK to make progress on the quarterly priorities.

E.g. If your quarterly goal is to close a major partnership with a single Fortune 100 customer, then ask your direct report at the start of a week what is it that they can commit to doing to moving that priority forward.

Example of chunking down the quarterly goal:

- If it’s the beginning of the quarter, the first week’s goal may be as simple as committing to identifying the 10 Fortune 100 customers your direct report is going to go after.

- The following week’s goal may be to telephone a contact at each of the ten Fortune 100 customers.

- In the week after that, your direct report may agree to commit to making a proposal to a certain Fortune 100 customer.

- Etc.

Now, as your direct report makes headway on these chunked-down goals, they will have a feeling of progress.

Remember this nugget of wisdom from my business hero Coach John Wooden (I’m paraphrasing):

Progress is not necessarily reaching your goal…progress is working as hard as you reasonably can on your goal and then letting the results be what they may.

4) Celebrate Milestones

When you reach your goals (i.e. milestones), take a moment to celebrate.

Acknowledge each and every person involved in the project…ideally with specifics on what they contributed to its success.

As a CEO, I ask my team to remind me of whenever anyone does something impressive…and then I try to write a quick congratulatory note to that team member (cc:ing their manager).

5) Acknowledge Failure As Progress

Don’t forget that failure is progress.

For example, your team may have a goal of trying to close certain types of customers or partnerships. If you explore one such deal and it’s not a good fit (for you or the other party), that is still progress.

Remember the old adage about the vacuum salesperson who realizes he has to knock on 50 doors before he makes a sale of one $50 vaccum:

“Each failure (closed door) is worth a dollar!” (because he gets $50 for knocking on 50 doors)

So when someone slams the door shut on a component of your goals, just move on — cuz you’re that much closer to getting what you want.

6) Be Authentic

This one’s easy: your praise of people should always be authentic.

Don’t tell someone they “really moved the ball forward” when you actually don’t know what they did.

7) Be Decisive

If you as a leader are indecisive about decisions around goals and priorities then you delay the feeling of progress that your team gets when they either reach (or fail to reach) their goal.

Progress is tough to feel when leadership is wishy-washy.

So be decisive about such things as:

- Setting goals

- Providing resources to help the goals get reached

- Pulling the plug on deals/losing deals (once in awhile you will either want to pull the plug on a deal or you will have it pulled for you by another party — this is ok, just make it fast).

If you can work on the above 7 tips, you will help motivate your team though progress.

4 comments so far (is that a lot?) | Continue Reading »

Tuesday, May 11th, 2010

Wow, Men Are More Popular Than Women On Twitter (& Other Interesting Twitter Demographics)

Tweet CommentFascinating study by Harvard Business Review looked at 300,000 random Twitter users and found the following demographics:

- Followers

- 80% of Twitter users have at least 1 follower

- 20% of Twitter users have no followers

- Men Versus Women

- 55% of Twitter users are women; 45% are men

- Men have 15% more followers than women

- An average man is almost twice as likely to follow a man than he is to follow a woman (despite there being more women on Twitter)

- An average woman is 25% more likely to follow a man than she is to follow a woman

- Volume of Tweeting

- The typical Twitter user has only Tweeted once in their lifetime

- 75% of Twitter users tweet once every 74 days

- The top 10% of Twitter users accounted for 90% of tweets

There’s some good Twitter demographics on the chart at A Look at Twitter Demographics.

And if you want to see Twitter demographics related to Web site traffic, go here.

If you’re into Twitter, you may also want to read How to Make Money On Twitter and How To Get Twitter Followers (Ones That Buy!).

No comments yet | Continue Reading »

Wednesday, March 31st, 2010

How To Innovate: 5 Tips From The Top Innovators

Tweet 3 CommentsI was fascinated by a recent Harvard Business Review (HBR) article on how to innovate (an abstract is here with the option to purchase).

They researched such innovators as Apple’s Steve Jobs, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, eBay’s Pierre Omidyar and Meg Whitman, Intuit’s Scott Cook and Proctor & Gamble’s A.G. Lafley.

Their key finding was that innovative entrepreneurs (who are also CEOs) spend 50% more time on five “discovery activities” than do CEOs with no track record for innovation.

I fully agree with these five tips for how to innovate; and want to provide my insights on them:

Five Tips On How To Innovate

1) Question (The Status Quo)

HBR points out that Michael Dell famously created Dell with the question:

“Why do computers cost five times the cost of the sum of their parts?”

Innovators are excellent at asking questions that challenge the status quo such as:

- Why not try it this way?

- Why do you do things the way you do?

- What if you tried this new thing or stopped doing some old thing?

- What would you do if failure was not an option?

2) Observe

Innovators are strong at observing people and details. …

3 comments so far (is that a lot?) | Continue Reading »

Thursday, February 4th, 2010

The 8 Mistakes To Avoid When Transforming Your Business

Tweet 4 CommentsIs part or all of your business in the need of a transformation — A truly radical change?

My smart friend Daniel Neukomm riffed on Harvard Professor John Kotter’s theories on mistakes commonly made in corporate transformations (hint: if you AVOID these mistakes, you can indeed transform your business) — enjoy!

Introduction

While a professor at Harvard Business School, John Kotter had the opportunity to gain valuable insight into an array of companies ranging in both size and scope.

In doing so, he identified eight key stages of transformational development in which companies failed to manage the change process. He theorized that those companies that had been successful did so only by effectively negotiating all eight steps.

He further noted that those firms who skipped any of those steps, or failed to recognize the importance of them were sacrificing quality and effect for speed of change, giving the illusion of being quick but in realty building a platform for failure.

In addition to illustrating a series of opportunities to fail, Kotter also provides some insight as to how to overcome these commonly experienced errors.

The Eight Mistakes To Avoid When Transforming Your Business

Transformation Mistake #1: Not Establishing a Great Sense of Urgency

The lack of a sense of urgency of transformation is the leading cause of why, and the primary stage of where business fail at effectively managing change.

Many companies struggle simply to be able to identify the need to change when circumstances arise that warrant doing so. Firms are constantly exposed to the need for change, from the emergence of new foreign markets to the presence of new, more powerful competition in the marketplace.

Kotter notes that more then 50% of companies fail at this initial stage for numerous reasons. Most notable of those significant reasons of failure at this early stage is the gross overestimation of current and prior efforts of urgency by corporate executives.

Many senior managers feel that they have already recognized and leveraged the existing need for urgent transformation and as such lack the necessary motivation to shift the rate of change into high gear.

Another important factor is the imbalance between those who dictate change and those who simply implement change. Firms with too many managers and not enough leaders often experience this dynamic and it adversely affects the ability to change efficiently.

Kotter’s Tips on Establishing A Sense of Urgency

Kotter offers the relatively simple solution of implementing mechanisms that establish a sense of urgency among employees. He further states that the need to aggressively achieve cooperation is essential as this impacts a firms ability to identify and discuss potential threats and pending crisis. The need to be able to clearly identify the market, and its competitive realities is also mentioned as a key solution to lack of urgency.

Transformation Mistake #2: Not Creating a Powerful Enough Guiding Coalition

Creating a powerful coalition is essential to guiding practical and effective transformation within a firm. The lack of importance placed on the need to achieve collective support is the second stage of error as cited by Kotter.

He states that in both large and small firms alike there is an increasing need to build support across a wide range of people involved in both the decision making and implementation process. Many firms believe that just having the senior management team on board with new ideas for change is enough.

In fact, there are many moving variable in the dynamic for change and as such many different roles, and the people who fill them, are required to achieve efficient transformational change.

For example, large firms undergoing aggressive transformation into a new market require the support of investors, board members and product development staff, but perhaps key customers as well.

Furthermore, due to the broad scope of support often needed to implement dramatic and effective change standard hierarchical structures are not enough to ensure success. (Kotter, 1995)

Kotter’s Tips on Creating a Powerful Coalition

Solutions to this stage of error range from instilling more power in those who already hold leadership roles, to the simplicity behind creating a more team oriented environment. (Kotter, 1995)

Transformation Mistake #3: Lacking a Vision

Lacking a vision can be an obstacle in almost any process, and most certainly in a corporate environment. Without a clear and defined vision it is not hard to imagine the difficulty experienced in trying to convey instructions and instill motivation in others to perform.

Furthermore, the lack of a clear and concise vision can be equally de‐habilitating, as broad sweeping goals can be difficult to break down into measurable achievements.

This lack of clarity can also trickle down into incompatible projects stemming from misdirected resources and undefined goals. (Kotter, 1995)

Kotter’s Tips on Strengthening Your Vision

Kotter offers some relatively straightforward and simple solutions to the absence of a clear and concise vision. Ensuring the existence of a vision is obviously at the top of the list as this is the source of the problem.

Many companies have visions that are bland and generic, often open to interpretation which in turn leads to misunderstanding.

Kotter suggests that having a vision that can be communicated clearly, to anyone, in less than five minutes is essential to having that vision realized.

Transformation Mistake #4: Undercommunicating Your Vision

The absence of an easily understandable vision can cause confusion in the workplace and hinder fluid change in any organization.

Even with a clear and concise vision, the ability to communicate it effectively to everyone in the company can is vital to facilitate its purpose.

Kotter points out three patterns in which companies fail to effectively communicate the vision.

- Many firms often attempt to utilize a single communication to instill a new vision in every employee, such as a meeting or an intra‐company memo.

- Corporate directors continuously repeat the vision through speeches to employees who often do not have a clear understanding of what is being stated.

- Both the vision and the corporate officers who communicate it to the employees can be clear and concise however those very same senior officers do not act in accordance with the vision. This combined effect often leads to the breakdown of implementation of the companies overall objectives, resulting in broad inconsistencies throughout the organization. (Kotter, 1995)

Kotter’s Tips to Effectively Communicating Your Vision

The most obvious solution to this issue is to implement a system whereby directors not only communicate the vision but also lead by example and execute the stated vision consistently.

Furthermore, all available vehicles should be utilized to deliver the vision to all stakeholders of the organization.

The solution to this potential issue seems rather elementary yet still is not widely practiced. (Kotter, 1995)

Transformation Mistake #5: Not Removing Obstacles To Your New Vision

Communication itself is not enough on its own to instill the goals laid out by the visions of the company to encourage and facilitate change. Numerous obstacles exist for corporate officers in their quest to see their visions brought to fruition through the actions of employees.

Major contradiction of interests seems to present the greatest barrier for progress, most notably incentive based performance pay structures. Many of these incentive programs reward individual performance over the performance of the company, presenting a difficult position for managers. (Kotter, 1995)

Carter’s Tips for Removing Obstacles To Your New Vision

Solutions for this problem lay in the design and structure of the system as it pertains to the vision of the company. No longer can a corporation have an aggressive vision and an incentive based pay structure that does not reflect the long‐term goals of that vision.

Designers of corporate incentives must take into account how the system may derail the likelihood of integrating the vision. (Kotter, 1995)

For example, if the vision of a health company is to provide medical treatment, incentive programs cannot be structured to reward saving the company money and reducing the bottom line by paying more to those employees who refuse to provide medical services.

Unfortunately, this is largely the practice of US medical insurance firms.

Transformation Mistake# 6: Not Systematically Planning And Creating Short-term Wins

Many companies experience turbulence in the transformation process by not creating short‐term goals. More firms have trouble in keeping employees motivated to achieve long‐term goals due to the lack of immediate return on efforts being made in the short‐term.

Kotter mentions that most people will not commit to the entirety of the project if there are not results in some measurable returns within the first 12 to 24 months.

If results are not seen within this immediate period, employees will often loose the drive necessary to achieve the long‐term goal. Managers who dissect such big picture goals into smaller more manageable tasks will often see greater results from their employees efforts implying that this may be an effective solution to the problems arising form lacking short‐term structure in the change process. (Kotter, 1995)

Kotter’s Tips on Planning & Creating Wins

Kotter offers some simple yet valuable insight yet again in this stage of transformational change by suggesting that managers break up longer‐term, more complex goals into short‐term, more manageable targets.

The creation of the short‐ term wins in this context so long enables a more momentum driven process, typically allowing for more accurate achievement of the longer‐term goal.

Establishing visible and more measurable performance improvements and then rewarding employees for achieving those milestones will enhance the corporation’s ability to implement change and realize transformational fluidity.

Transformation Mistake #7: Declaring Victory Too Soon

While establishing short‐term wins is key to the success of managing change there are also some disadvantages which can arise form this strategy as well. Kotter points out while short‐term wins are encouraged there is some danger in give incentives to employees to reach a larger volume of small scale project achievements.

This danger arises from employees and managers alike striving for accomplishments that have emotional and financial bonuses attached because there will be a need to declare victory sooner than what is best for the organization.

There is an ironic relationship between those who resist change and those who support stated in Kotter’s theory. He mentions that while change initiators are quick to declare themselves victorious in their ability to effectively manage change is often the change resistors who step in an solidify a failure.

This is due to the fact that such resistors are looking for any opportunity to stop the change process and declaring victory provides that opportunity.

Kotter’s Tips on Declaring Victory

In an effort to solve the issues surrounded by premature victory celebrations Kotter points out that managers should focus instead on their increased credibility to implement change into systems, structures and policies.

Moreover, managers should promote those employees who recognize and implement the vision of the organization, establishing a momentum driven transformation process and achieving long terms goals rather then racking up points on a project score board.

He further states that the transformational process needs to be constantly reinvigorated with new projects, themes and new agents to implement them in order to capitalize on momentum.

Transformation Mistake #8: Not Anchoring Changes in Your Corporate Culture

Perhaps the most interesting error mentioned by Kotter is the inability of a corporation to solidify whichever new process of change deemed effective.

Many firms fail to ensure that years of efforts not be flushed away by a lack of recognition by all employees, including top managers of reasons why change has been

successful.

On many occasions companies failed to ensure that new behaviors were integrated and relied on in the future.

Two important factors are noted for this lack of integration.

- Many firms fail to show exactly how the previous change efforts have lead to enhanced performance, leaving the many to make this connection on their own. This can lead to assumptions, or worse, lack of recognition all together as to what aspect of the transformational process were successful and why.

- The second factor rests arises when successful change management is not integrated into new management successors. If a successor does not fully grasp the importance, understanding and simple foundations of how and why transformational efforts where successful within the organization he/she can wipe out much if not all of the progress generated under previous management.

Kotter’s Tips on Anchoring Change

Solutions to this problem are readily available to managers.

In the former, simple efforts to communicate the reasons for successful transformation should be made to ensure a clear, broad, company wide understanding of the reasons for success.

An example of this would be the use of company newsletters outlining the relevant information necessary to understand achievements and why they were possible so that al employees can identify opportunities for future success.

In the latter, ensuring that the board of directors understands the reasons behind why a company leader was able to enhance performance through successful change is imperative to ensure that effective processes of change continue under new management. (Kotter, 1995)

Bibliography and References

- Change Management Class Notes. (June, 2008). International School of Management. Paris, France.

- Kotter, John P. (1995, April). Why Transformational Efforts Fail. Harvard Business Review.

- Senge, Peter M. (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. , Random House Publishing, USA.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also want to check out Daniel Neukomm’s other pieces such as: Why The Home Page Is Dying and Porter’s Five Forces.